Voting results in the recent Turkish elections recapitulate ethnic boundaries of the past

How ethnic distributions of the past leave their mark on present political patterns.

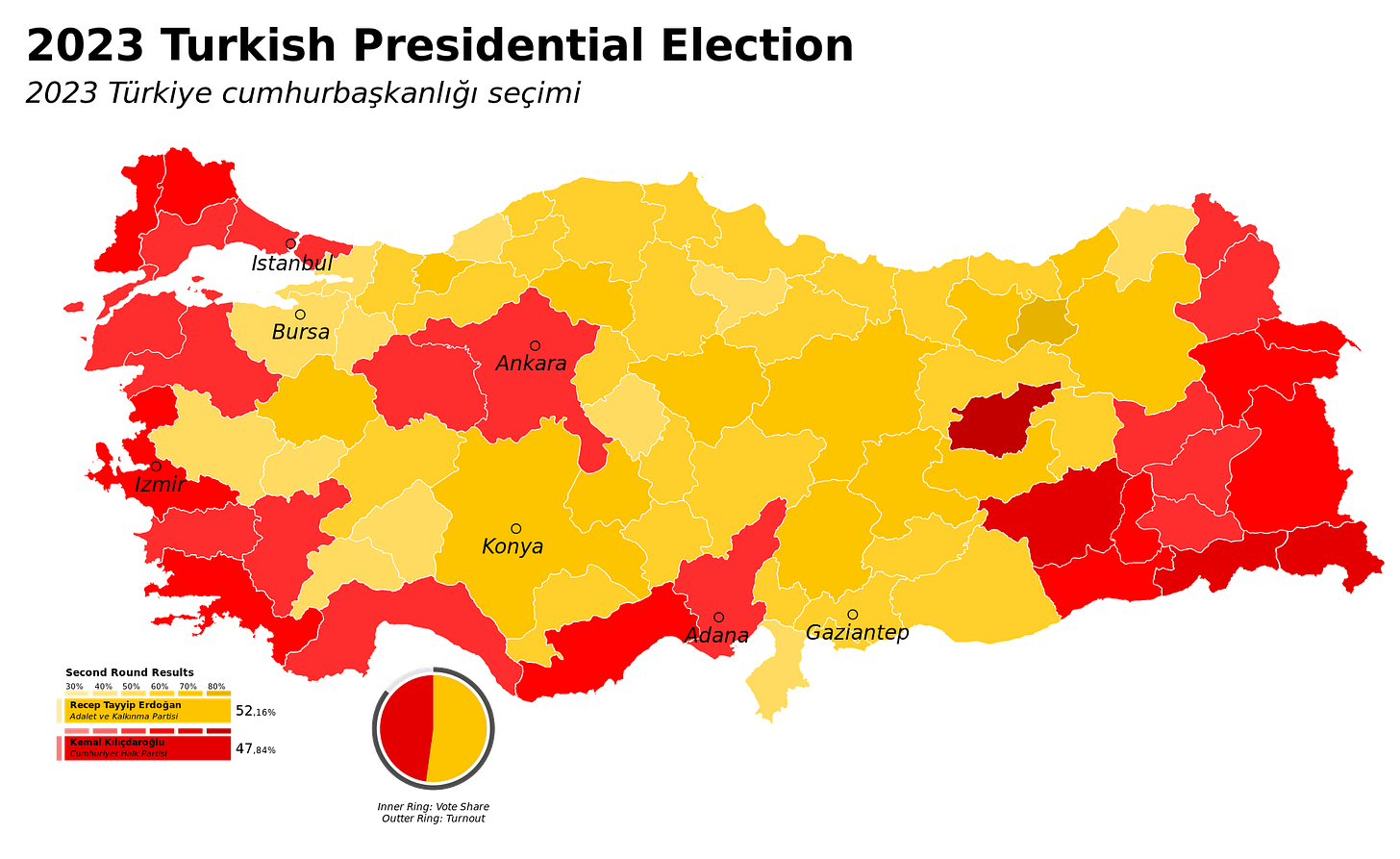

An insteresting observation about the recent presidential elections in Turkey is that the voting patterns roughly recapitulate the historical ethnic distribution patterns that existed in Anatolia until the early decades of the 20th century.

As one can see from the map, the provinces that voted overwhelmingly for Erdoğan (yellow) roughly comprise the territory that was allocated to the Ottoman Empire/Turkey by the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) at the end of World War I, which at the time were the regions where Turks constituted the majority. The only exceptions disturbing this pattern on the map - i.e., the red islands in the sea of yellow are the capital Ankara with the neighbouring city Eskişehir, and the province of Tunceli. Regarding the former, Ankara was a tiny town prior to 1923 when it was proclaimed the capital of the new Turkish republic. It gradually grew into a metropolis only much later. Hence with the general tendency of big urban areas voting liberal the result should come as no surprise. And Tunceli is the hometown of the opposition candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, which might explain why he won the vote there too.

Now, let’s look more closely into the regions in the east and west where Kılıçdaroğlu had an edge over his opponent. In the eastern and northeastern provinces of present-day Turkey Armenians constituted either the majority or represented a sizeable minority prior to the Armenian Genocide in 1915. By the Treaty of Sévres they were ceded to the new Armenian Republic that was proclaimed in 1918. However during the Turkish-Armenian War of 1920 Turkey recaptured those territories. The remaining Armenian population was either massacred, expelled or was forced to flee.

The northwestern regions corresponding to East Thrace and western regions centered around the city of Smyrna (Izmir) were ceded to Greece by the terms of the treaty. They had a Greek majority at the time. Moreover, the Zone of the Straits with the capital Constantinople, another region with a Greek majority or sizeable minority, was temporarily put under British jurisdiction with negotiations underway to transfer it to Greece at a later timepoint.

However, during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922 Greece lost those territories to Turkey. And needless to say the likely transfer of Constantinople with the Zone of the Straits to Greece never materialized. The fate of the native Greek population of western provinces was the same as that of Armenians in the east - massacre and expulsion. The remaining Greek population was later transferred to Greece as part of the population exchange agreement between the new Turkish Republic and Greece.

Kurds constituted the majority in the southeast, but unlike Christian Greeks and Armenians have been mostly spared the large-scale ethnic cleansing and therefore continue to predominate in those regions up until today, which explains the voting results.

In spite of the western regions of Turkey being cleansed of the Greek population and later repopulated with new arrivals from the central (ethnically Turkish) regions of Anatolia, even after many generations they remained largely pro-western and have consistently been the most liberal provinces during the modern Turkish history. The city of Izmir, for instance, from the very beginning has been the stronghold of anti-Erdoğan opposition even at the height of Erdoğan's popularity. In the 2000s and early 2010s Erdoğan would win even in Ankara and Istanbul but consistently lose in Izmir. And in general the inhabitants of Izmir have always been famed for their liberal attitudes and secularist stance.

This is actually an interesting phenomenon observed in other countries too where certain regions/provinces historically had a different native population from the one currently residing in it. For instance the western/north-western regions of Poland (Silesia, East Brandenburg, Pomerania, West Prussia) historically had an absolute German majority and became Polish only at the end of the Second World War. In the process, the German population was expelled and replaced by Poles arriving from the east.

But it seems the historically non-Polish nature of those western regions makes itself felt up until the current day, in spite of the fact that their ethnic make-up has been homogenously Polish like the rest of Poland for the last 70 years. This distinctness manifests itself most acutely in the voting patterns. In the last Polish parliamentary elections, for instance, those former German regions voted overwhelmingly for the liberal opposition represented by the Civic Platform, whereas the rest of Poland voted for the national-conservative incumbent Law and Justice Party.

These examples are of course not at all exhaustive of this general phenomenon and only the ones that appear the most conspicuous to me. A similar pattern can be observed throghout Eastern Europe in the regions where Germans constituted the majority or represented a sizeable minority prior to 1945.

What can be the reason for this recurring phenomenon where the current populace in the regions with a long history of formerly being populated by another ethnicity somehow shows political and cultural preferences distinct from their co-ethnics in the "core" regions of that ethnicity?

One explanation can be that the extinct ethnicity leaves its genetic mark on the region, after all, even after being ethnically cleansed completely. Ethnic Greeks and Armenians who would have converted to Islam and taken Turkish names would have certainly escaped genocide and expulsion, for instance. The same can be said about ethnic Germans who spoke Polish and took Polish names at the time when eastern German territories were ceded to Poland. Mixed marriages were also definitely a contributing factor to the extinct ethnicities leaving their genetic marks on their ancestral regions. This could very well explain the feeling of distinctness of the local population in the decades to come, together with their distinct cultural and political preferences, which at times are diametrically opposite to the preferences of the rest of the country. As we can see in the cases of Poland and Turkey, for instance, people in ancestrally Polish regions or in regions with a longer history of Turkish majority than the rest of Turkey tend to be more nationalist/conservative whereas those in regions that had a significant presence of other ethnicities in the past tend to be more liberal within the context of the overall societal preferences of their respective countries. The "call of blood" can be very powerful after all.

Another reason might be that the cultural heritage left by the extinct ethnicity in the region was so powerful that it permeated the new arrivals whereby they were thoroughly imbued by it with a lasting transgenerational effect.

It's a common thing in western regions of Turkey, for instance, to take pride in a Greek great-grandfather or great-grandmother. Or from what I also know, inhabitants of Vojvodina in present-day northern Serbia, which was part of Austria for approximately 200 years until 1918 and had a sizeable German minority up until 1945, feel distinct from the rest of Serbia and take pride in their distinctness, although they belong to the same ethnicity as the population of the rest of the country.

It's therefore fascinating to witness how ethno-cultural distributions of the distant past leave their marks on the preferences and behavior of the present.